The first surviving record of Jewish-owned houses and a synagogue in Marburg dates from 1317. They were located in Judengasse above the market square. An older house served as the synagogue; around 1280 it received a vaulted room whose cap stone was graced by a star of David.

This synagogue was destroyed in the great fire that swept the city in 1319, but was rebuilt afterwards. Nevertheless, the Jewish settlement perished during the 14th century owing both to the plague and to pogroms; in 1452 the remnants of the synagogue were used as materials for the construction of a city wall.

In 1536 two Jews were admitted to the city. However it was not until after the Thirty Years’ War that Jews took up permanent residence in the city; until 1720 their synagogue was located opposite the medieval one in the upper storey of a Jewish dwelling. In 1744 a mere six Jewish families were registered as residents, who had a prayer room in Langgasse, again in the top storey of a Jewish-owned house. Since this room was soon overcrowded, the community, in 1818, bought a house in Ritterstrasse where it established its synagogue.

The annexation of Hesse by Prussia in 1866 initiated a trend upward not only for the city as a whole but also for the Jewish community. Numerous Jewish businessmen and bankers took up residence in Marburg, and the city was made the seat of the provincial rabbinate. Depite the agitation of the Marburg citizen Otto Böckel, who was elected to the Reichstag as its first openly antisemitic member in 1887, the community continued to grow. In 1888 it consisted of 298 persons; the synagogue, however, could only accommodate 89 men and 64 women, and accordingly a new place had to be found. After a prolonged search for a suitable plot, the community was able to acquire a tract of land at Universitätsstrasse located between the emerging new housing area of the “Südstadt“ and the old part of town.

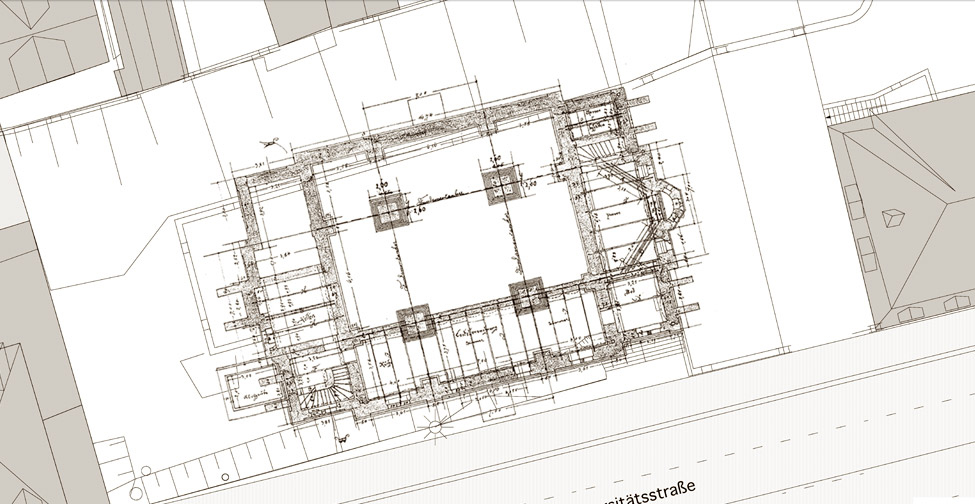

The local architect Wilhelm Spahr was commissioned with the planning of the new building. He designed a symmetrical two-storey building situated parallel to the street. Its centerpiece, measuring 16 x 16 m in diameter, contained the assembly room emphasized by its height and a cupola; it could seat 230 men on the ground floor and 175 women on the gallery. To the west there was a wing for the main entrance, above which the school rooms were located; to the east a wing housed the dais and the torah shrine. The basement floor accommodated the living quarters of the synagogue warden and the mikveh.

The facade was covered in red sandstone offset by two fascia of light sandstone; the octagon-shaped cupola was roofed with yellow-glazed tiles, its apex graced by a star of David. The design of the facades was heavily influenced by late Rhenish Romanesque architecture – apparent especially in the semi-circular arch friezes and rosette windows – but also incorporated various Moorish elements such as cusped arches and horseshoe-shaped apertures. Thus the architecture of the Marburg synagogue adhered to the “German national style“ then current for sacral buildings without sacrificing the reference to the fertile Jewish cultural history in Spain; no other religious building in Marburg at this time boasted a cupola. The synagogue was an emblem of the community’s economic clout and of its self-conception in surroundings defined by Christian traditions. In 1897 it was consecrated amid great public interest.

In 1905, the Jewish community had grown to 512 members. In 1901, an institution for pupils and apprentices located in Schulstrasse was opened. At university there was also a Jewish corporation; a Jewish canteen and a Jewish hotel (ironically numbering Roland Freisler, later to become the presiding judge of the Volksgerichtshof, among its guests) were found in the city. Several Jewish professors taught at the university, yet the hope that the rampant antisemitism there could be overcome proved illusory; the university remained a hotbed of reactionary ideologies. Soon, however, many members of the community left Marburg, mainly for Frankfurt; the community became impoverished to the point that, in 1922, bills accounting for about 40% of the total cost of the construction of the synagogue were still outstanding.

Elmar Brohl